Fire on the Prairie is about Harold Washington, who went from being born by the stockyards, to Springfield, to US Congress, and got elected as the first Black mayor of Chicago. Washington died in 1987, only a few months after being reelected.

I admit I haven’t read many books, but this one, I think, has one of the best hooks. The title is based on a quote from Martin Luther King Jr:

In 1965 Hosea Williams, a member of King's advance team, arrived in Chicago boasting that the SCLC would register a hundred thousand new black voters. When they came nowhere near that goal, when they fell more than ninety thousand voters short. Williams left muttering aloud whether blacks in Chicago wanted to be "freed." Only in Chicago had the local black leadership called a press conference telling King and the SCLC to go back to the South where they belonged.

King, too, questioned black Chicago's hunger for freedom. But where Hosea Williams left disgusted. King cast Chicago as a great challenge, a bellwether of wider possibilities. "If we crack Chicago," King said, "then we crack the world." Black empowerment in Chicago, he pro-claimed, "would take off like a tire across the land."

I really enjoyed the book. Fire on the Prairie starts off with a firehose introduction to Chicago politics. Chicago politics has two main characteristics. The first is the machine, the second, racism.

When Harold ran, the (white) machine politicians turned against him, appalled that a Black man was running for mayor. At a Jane Byrne rally during the primary, an alderman said “it’s a racial thing, don’t kid yourself.” The Black machine politicians wasn’t thrilled either, but opposing his candidacy meant certain political death.

The Democratic machine pulled every stop to ensure a Black man with anti-machine fixings would not win. Rivlin maps out four sections of the city – the Black south and west sides, the white liberal lakefront, and the white ethnic working class southwest and northwest sides4.

The racists and the machine (and those racists in the machine) needed savior. They decided they could stomach the (white) Republican candidate, Bernard Epton. Rivlin paints him as not unexpecting, in the unfortunate position of being backed by the Democratic machine. Alas, he picked up the convenient campaign phrase of “Epton—Before It's Too Late.” Epton racked up more democratic endorsements from ward committeemen1 than Harold did. A reporter called a promiment alderman’s ward office, pretending to be a confused voter, and was told by the woman answering the phone that “all of us here are voting for Epton.”

Rivlin points out in over a dozen anecdotes that Epton supporters very much dipped into racism, even if Epton himself never said anything explicit. If Harold appeared in southwest or northwest neighborhood, they followed to rally against him. They would speak candidly to the news about not wanting an n-word mayor, hold up signs about white pride, or wear t-shirts that said “VOTE WHITE, VOTE RIGHT.”

Anthony Laurino, another Democratic committeeman, also supported Epton. Laurino scoffed when a reporter asked if his support for Epton boiled down to Washington’s legal troubles. “The people in my area,” Laurino said, “just don’t want a black mayor—it’s as simple as that.” Another southwest side official, choosing the cover of anonymity, explained for a reporter that whites in his part of the city had been “pushed out of their neighborhoods two or three times by blacks. This is a chance to get even.”

Harold ended up winning with 51.7% of the vote. Byrne won in 1979 with 82.1%, not an uncommon margin in a Chicago general election, so a whole lot of Democratic voters crossed over to vote against Harold Washington.

I am not an expert on books, so it is hard for me to “review” one. But before I explain why Harold was so important, and what I think he means for us now, I will point out some things.

Rivlin includes an entire chapter about Leanita McClain, the first black person on the Tribune editorial board, who committed suicide due general depression which was exacerbated by the hatred she discovered from her colleagues during the Washington campaign (read “How Chicago Taught Me How to Hate Whites”). He also expends significant effort dumping on Jesse Jackson. Per Rivlin, Jackson is a bad organizer with no followers, whose saving grace is his is media-savvy and extreme readiness to talk to the white press. When an actual organizing group needed to do something, Jackson’s organization would offer up their space, as long as their name could go on it. When Washington won his 1983 race, and Rivlin paints the entire staff as trying to do everything to get Jackson out of the campaign, Jackson still found a way to squeeze himself into the photo.

I don’t want to retell the story of Harold, because the book does it much better. The book does not actually tell you much about Harold’s thoughts. He didn’t have any children, and didn’t have many friends. The friends he did have were either hardly cited, or were political. He was a deeply political guy. He just seemed to enjoy it. He would spend all his time either being a politician or reading books, and he took no care to his physical appearance or being timely. He was also a really good politician. Despite being basically being elected by the machine, he didn’t use the “idiot card” that legislators were supposed to follow on how to vote. He bucked the party strategically.

Rivlin paints Harold as a pragmatist. I think he was grudgingly so. In his 1983 campaign, he was gung-ho, talking about radical issues in radical ways. In 1987, he was staid, calm, and trying to show voters that he is the stability they really want.

I think the lesson we can learn from Harold today is a political lesson. Politicians do not have to sell themselves out, full stop. At no point during his political career was anyone able to label Harold a sellout. Even when he and Lu Palmer grew apart, at least in Rivlin’s telling, Palmer was clearly frustrated that people would listen to Harold and not him.

He wasn’t a sellout, though. He was strategic. His biggest failing was probably not taking care of his health and deteriorating over the course of his mayoralty, and like many great men, did not cultivate a clear succession to his movement. And his movement was very fragile. Even when he his body was still cooling from death, members of his coalition defected and there was an intra-Black-caucus battle over who would become the next mayor. In a sad way, his death was similar to his life, mired in politics. An insane statistic from his death is that as all five local stations covered the council meeting to select the replacement mayor into the night, at 2AM, Nielsen estimated 480,000 people were still watching.

The next mayor, Bill Sawyer, was the candidate the black and white machinists could get over the line. With 24 white machinists, they needed just two more votes to win, and a Black candidate was strategically beneficial. In just 15 months, he would face a special election. With a divided black community, electing whichever machine candidate2 was desired would be a layup.

I also think it is tough to judge Harold on the terms of his administrative capabilities. He was a much better politician than administrator, but he wasn’t horrible at administration. He made some missteps, but Rivlin points out that he ran a good budget, trimmed the patronage army, nominated people of color and women to appointed positions, and tried his best to execute on his campaign goals. For the starting bulk of his first term, the machine still held 29 seats, and The 29 took every opportunity to defer, delay, stall, poison, and block any initiative3 that came from Harold and the mayor’s office. By the end of his term, Rivlin paints his team as gaining steam and ready to keep on their path. Sadly for us living 38 years later, we never got to see the fruits.

At the end of it all, what we learn from Harold, in my opinion, is a politican who can listen to the people, read the history, read the books, understand the strategy, and allow his supporters and staffers to unleash their creativity for a genuine cause can tap into the people’s hope. Unfortunately, aligning all these incentives is nearly impossible, hence why it needed a “great man” to get it into order. Chicago is a masterclass in misaligned incentives. Instead of chasing power, Harold made strategic tradeoffs to both gain power and propel a positive agenda that voters wanted. Some people focus too much on the agenda, whether voters like it or not. Others, like the machine, focus on just chasing power.

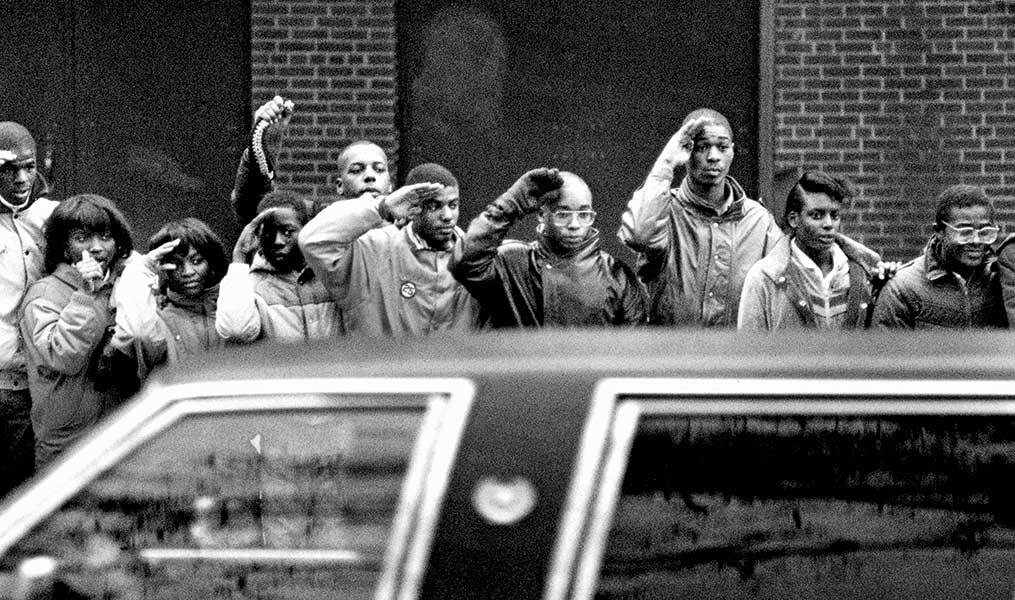

South side students salute as Harold’s casket is driven past (source)

The book never really tells you why Harold did all of this. But people loved him. Ten thousand people attended his funeral between two to five hundred thousand people viewed him as he lay in state. Only 25,000 came for Elvis.

His mourners were not sobbing women throwing themselves at the foot of the king’s sepulcher but people of all races and ages who abandoned themselves to spontaneous and unrestrained grief. In interview after interview reporters heard the same words from the men and women who attended the funeral. They spoke of Washington as a favorite uncle or a father figure. Love was on people’s lips, and it was also written in thick letters on cut-up cardboard boxes. GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN, WE LOVE YOU HAROLD, one homemade sign read. A bearded white man wearing round wire-frame glasses held on his shoulders a child who held a pennant that read THANK YOU MR. MAYOR. WE ALL LOVE YOU.

Rivlin begins by asking what does love have to do with politics. I think it has to do with what Harold signified. He wasn’t in it for power, and you can’t say he tried to hijack the system for his own gain. He never abused people’s shortcomings. His followers felt like he truly just wanted to make a city for all the people.

When a leader loves their people, the people will love them back. Chicagoans loved Harold.

The police officer standing guard at City Hall on the day Harold died (source)

1 Ward committeeman are the leaders of the Democratic machine in the city’s 50 wards, plus a few wards in the other cities in Cook County. The machine is the Cook County Democratic Party.

2 Richard M. Daley ended up winning this election. I do not yet know if he was the machine’s candidate, but it doesn’t seem like malevolence to assume that Richard M. Daley, son of Richard J. Daley (subject of books named things like Boss and American Pharoah), was the machine candidate.

3 One of the early initiatives they tried to block was allocation of funds for the Byrne-approved O’Hare expansion (which included Terminal 1 and the ATS). The 29 eventually buckled after pressure, but that does not mean they lost.

4 At this point, there was a rapid growth of Latino population, especially in the southwest and northwest, but in 1983, they weren’t playing a huge role. By 1987 they were very relevant.